EL-DE House in Cologne Former Gestapo prison: 13 steps down

Cologne · The series "Cologne below" directs the eye to special places in the Cologne underground. Between 1935 and 1945, prisoners left moving inscriptions on the cell walls of the EL-DE House in Cologne.

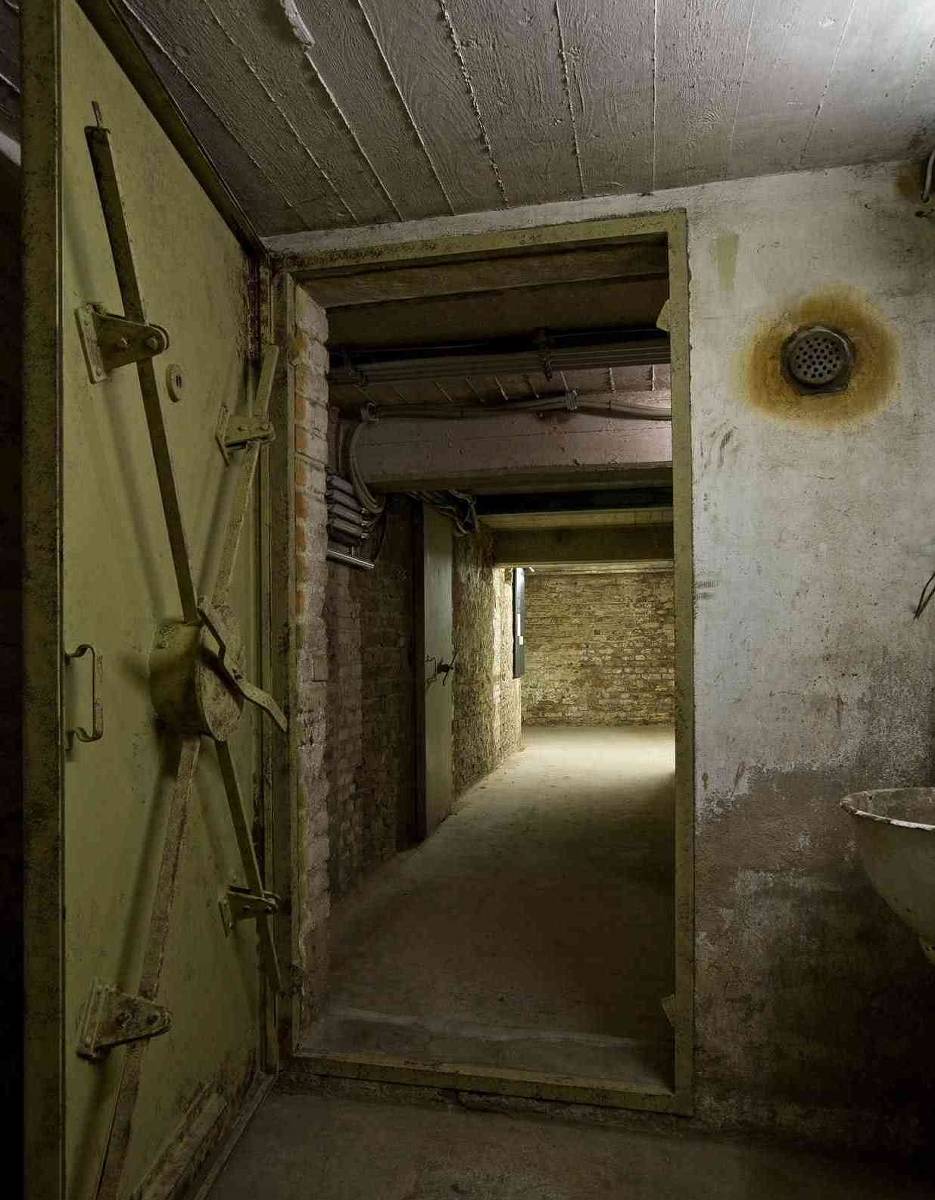

To the right of the stairs there is a corridor which branches off to the left, here the marble tiles end. Behind it only bare concrete. 13 steps lead down, at the end of the stairs you pass an iron grid. One cell follows the next. Sketches, individual sentences, dates - on the cell walls there is a piece of history from 1935 to 1945. History told by prisoners themselves.

At that time the EL-DE-House in Cologne served as the headquarters of the Secret State Police, or Gestapo for short. The officers set up a house prison in the basement. Here the prisoners waited for their interrogation and left over 1800 inscriptions. An impressive documentation of their experiences, thoughts and stories.

"We are facing the gallows, sorry to be separated from my beloved husband and from the wide world," reads one of numerous inscriptions. Long letters or isolated sentences are written on the cell walls, portraits are painted, sometimes only initials or dates. Some are clearly recognizable, others faded. "Various objects were used, mostly what one had at hand: pencils, pieces of charcoal, even lipstick. Some inscriptions were also carved into the wall with cutlery, iron nails or fingernails," says Werner Jung, director of the NS Documentation Centre. Over 600 inscriptions are written in Cyrillic, many others in French, Polish and Dutch. "This shows that the inscriptions are primarily from prisoners of war and forced laborers who were held here at the end of the war," explains Jung.

At the beginning of the National Socialist regime, the Gestapo had mainly targeted political opponents, later also prisoners of war and forced laborers. "It can be assumed that over 400 prisoners were hanged in the inner courtyard of the EL-DE House.“

The conditions under which the prisoners lived are unimaginable today. Imprints of two iron flatbeds can still be seen at the bottom of some cells. The ten prison cells, each six square metres in size, are intended for one to two people. A French inscription, however, proves that this requirement was not followed exactly: "The German usage reveals itself especially in cell six, where they managed to keep up to 33 people at once.“

The inmates thus documented the conditions under which they had to live. "We have a direct tradition here," says Jung. "This is unique in Europe in this form."

The inmates who wait in the cells for their interrogation also write about their lives. In this way even individual fates can be researched and reconstructed. "For example, there is the story of the French woman Marinette, who follows her boyfriend to Germany," says Jung. Marinette worked for a German family as a housemaid when they are arrested as opponents of the regime. The pregnant Marinette is also arrested, her daughter Christiane is taken away from her in hospital after her birth. "I can no longer live without my little daughter, I think I'm going mad in this house," Marinette writes on the cell wall. It was not until 1987 that Marinette and her daughter Christiane could be found in the French media.

"The prisoners were tortured by the Gestapo in the deep cellar in order to force confessions. The other inmates could hear the screams," says Jung.

The value of the inscriptions can only be recognized late in the post-war years. After the end of the war, the building was occupied again by tenants, including the city of Cologne, which set up the registry office and pension office there.

Used as a storeroom

Some cells were used for years as a storage room for files and folders, the inscriptions remain so intact behind the shelves. "For us, of course, this is a huge stroke of luck," says Jung. It was not until the early 1980s that the inscriptions were uncovered, restored and then deciphered. The interest in a processing and clarification had not been particularly large before, says Jung and shrugs his shoulders. In 1991 a memorial was finally inaugurated, and in 1997 the permanent exhibition "Cologne under National Socialism" was opened on the first two floors of the building. "Before 1980, the building could have been demolished, walls demolished or painted over. Fortunately, this has no longer been possible since then due to the protection of historical monuments".

While other museums try to bring history to life with multimedia contributions such as sound effects, Werner Jung refrains from such technical gimmicks. "Here it is not even remotely necessary to create a depressing atmosphere with artificial effects," he says. "The place works of itself.

The Series

The series "Köln unten" („Cologne below“) is a cooperation between students of the Cologne School of Journalism and the Bonner General-Anzeiger. The young journalists have visited places in the Cologne underground for our Rhineland page. Among other things, they discovered art in the sewers and explored the tunnel under the airport.

Info

The EL-DE House is showing the special exhibition "Everywhere Luther's Words..." until February 24.

Martin Luther in National Socialism. The EL-DE-Haus, Appellhofplatz 23-25, is open from Tuesdays to Fridays from 10 am to 6 pm. On Saturday, Sunday and public holidays from 11 to 18. Adults pay 4,50 Euro entrance fee, concessions 2,00 Euro.

Original text: Sophie Scholl

Translation: Mareike Graepel